Category Ramblings on Space and Time

Hubble Space Telescope discovers fourteenth tiny moon orbiting Neptune

From the Melbourne Herald Sun:

NASA announced the discovery of Neptune’s 14th moon Monday. The Hubble Space Telescope captured the moon as a white dot in photos of Neptune on the outskirts of our solar system.

The new moon – Neptune’s tiniest at just 12 miles across – is designated S/2004 N 1.

The SETI Institute’s Mark Showalter of Mountain View, California, made the discovery. He was studying the segments of rings around Neptune when the white dot popped out, 105,251 kilometres from Neptune. He tracked its movement in more than 150 pictures taken from 2004 to 2009.

The considerably bigger gas giant Jupiter has four times as many moons, with 67.

Comet ISON Observer’s Workshop Set for Aug. 1-2 at Johns Hopkins APL

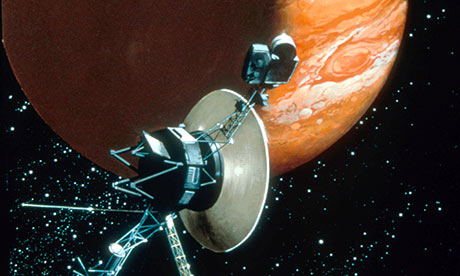

Voyagers 1 and 2

Most people reading this blog are probably younger than I am and haven’t heard of the Voyager program. They were a pair of probes launched in the mid 1970’s, each powered by a small reactor, that have explored the Outer Solar System and now are headed for interstellar space.

This is a link to images of Voyager and what it’s taken of the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. It’ll be informative and enjoyable to see what mankind has accomplished.

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/imagesvideo/imagesofvoyager.html

Voyager 1 spacecraft’s latest find takes the edge off the solar system

per:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/jul/09/nasa-voyager-solar-system-edge

-

Joel Achenbach for the Washington Post

- Guardian Weekly, Tuesday 9 July 2013 08.59 EDT

The edge of the solar system has no edge, it turns out. It has a fuzzy transitional area, not quite solar system and not quite interstellar space.

This basic fact of our star’s environment has been discovered byVoyager 1, one of the most remarkable spaceships ever built. Our premier scout of deep space, Voyager 1, is currently 11bn miles from the sun, beaming data to Earth as it scoots at 24,000kmph toward the constellation Ophiuchus.

Scientists had assumed that Voyager 1, launched in 1977, would have exited the solar system by now. That would mean crossing the heliopause and leaving behind the vast bubble known as theheliosphere, which is characterised by particles flung by the sun and by a powerful magnetic field.

The scientists’ assumption turned out to be half-right. On 25 August, Voyager 1 saw a sharp drop-off in the solar particles, also known as the solar wind. At the same time, there was a spike in galactic particles coming from all points of the compass. But the sun’s magnetic field still registers, somewhat diminished, on the spacecraft’s magnetometer. So it’s still in the sun’s magnetic embrace, in a sense.

This unexpected transitional zone, dubbed the “heliosheath depletion region,” is described in three new papers about Voyager 1 published online last month by the journal Science.

“There were some surprises,” said Ed Stone, who has been the lead scientist of Nasa‘s Voyager program since 1972. “We expected that we would cross a boundary and leave all the solar stuff behind and be in all the interstellar stuff. It turned out, that’s not what happened.” So, how big is this transitional zone at the edge of the solar system?

“No one knows,” said Stone, 77, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology and the former head of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Voyager’s home base. “It’s not in any of the models. We don’t know. It could take us a few more months, it could take us several more years to get through it.”

The dimensions and nature of the heliosphere are not a wholly esoteric matter. The sun’s magnetic field deflects much of the radiation coming from other parts of the galaxy that was created in supernova explosions. Interstellar space is not a benign environment. The heliosphere’s features make life easier for blue planets such as Earth.

Voyager 1 can be counted as one of the great exploratory craft in history, and none has gone farther, nor cruised steadily at such astonishing speed (a few have briefly gone faster while falling into the sun). Two Voyager probes were launched in 1977. Both spaceships carried a gold-plated record crammed with digital information about human civilization, including mathematical formulas, an image of a naked man and woman, whale vocalizations, and clips of classical and rock-and-roll music. (The famous joke was that the aliens listened to the record and replied, “Send more Chuck Berry.”)

The two Voyagers embarked on what was called the Grand Tour, taking advantage of an orbital positioning of the four outer planets that happens less than once a century. Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn before angling “north,” as astronomers would describe it. (There’s no up or down in space, but there is a north or south relative to the orbital plane of the planets.) Voyager 2 went past Jupiter and Saturn and flew by Uranus and Neptune before heading “south.”

The images of those planets and their moons, now taken for granted, were stunning triumphs of the Voyager mission. And in 1990, Voyager 1, nearly 4 billion miles from the sun, turned its camera toward Earth and took an image of what Carl Sagan called the “pale blue dot” of our home planet.

Now Voyager 1 is 124 astronomical units from the sun – one AU being roughly the mean distance from Earth to the sun, or about 150m kilometres. Voyager 2 is at 102 AU.

These spacecraft are not immortal, even if sometimes they act like it. They have a power supply from the radioactive decay of plutonium-238, which generates heat. The half-life of that system is 88 years. Small thrusters occasionally are fired to keep Voyager 1’s 23-watt radio antenna pointed toward Earth, where the faint signals are picked up on huge arrays of radio telescopes in the United States, Spain and Australia. But Stone anticipates that weakening power will force scientists to start shutting down scientific instruments on Voyager 1 in 2020 and that by 2025, the last instrument will be turned off.

“It changed the way we view our place in the cosmos,” said Bill Nye, the “Science Guy” who is chief executive of the Planetary Society in Pasadena, Calif. He said the new discovery by Voyager 1 is a classic example of why we explore: “What are you going to find over the unknown horizon? We don’t know. That why we explore out there.”

NASA’s associate administrator for space technology, Michael Gazarik, said of Voyager 1’s durability: “It is amazing, especially in the harsh environment of space. This piece of hardware has a life of its own.”

In 40,000 years, Voyager 1 will be closer to another star (with the romantic name AC+79 3888) than to the sun. And then what? It will just keep going – a silent, dark craft on a seemingly eternal journey.

“It will be orbiting the center of the Milky Way galaxy essentially for billions of years, like all the stars,” said Stone of what has been, for him, the spacecraft of a lifetime.

Disks don’t need planets to make patterns, NASA study shows

Hubble finds a true blue planet: Giant Jupiter-sized planet located 63 light-years away

Spaceflight Now | Breaking News | Hubble sees comet ISON bringing holiday fireworks

Comet Ison brightening fast

Per catholic.org

Comet ISON is still aiming for a spectacular showing this November as the comet continues to brighten rapidly. The celestial visitor is now between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter and may become one of the brightest natural objects seen in the nighttime sky.

Comet ISON is about 3.1 miles in diameter and traveling at a speed of 48,000 MPH. The comet is being watched by an increasing number of instruments as it brightens. Large, professional telescopes on Earth are tracking the object as well as space telescopes and major observatories.

By September, the comet should brighten enough to be spotted with most backyard telescopes and large binoculars. Eventually, the comet will be visible to the naked eye in November.

After that, it will continue to brighten as it rounds the sun on November 28, although it may not survive this approach, passing just 1.1 million miles from the surface of the Sun. At that close proximity, scientists think the comet could break into pieces.

Assuming ISON survives, it will remain visible on its outbound journey, with naked-eye observers enjoying the sight until mid-January. It should be easy to spot in telescopes until March.

On the night of January 14-15, Earth will pass close to ISON’s orbit, and may be dusted with fine particles from the comet. These particles are thought to be too small to spark a meteor shower that will be visible to the naked eye, but the dust could create high-altitude clouds that glow after sunset because of their height above the Earth’s surface. These are known as noctilucent clouds.

Comet ISON is expected to put on a spectacular show, even if it breaks up near the Sun. The current rate of brightening is on track for a -17 magnitude performance, which would make it brighter than the full moon. However, scientists think this pace of brightening may slow as it approaches the Sun, and it’s more realistic the comet will peak around -7 magnitude, which is closer to Venus in brightness. Experts warn that comets can often perform well below expectations, so betting on its performance is more guesswork than science.

Other questions remain about ISON. For example, its orbit appears to be very similar to that of the Great Comet of 1680, which was itself visible in the daytime sky. Astronomers have suggested that ISON may be a fragment of this comet, or rather than both comets share a common parent.

It is hoped that the appearance of Comet ISON will awaken imaginations around the world, and pique interest in astronomy for a new generation.

Warp Drives Aren’t Just Science Fiction

TechNewsDaily recently caught up with Davis to discuss his new paper, which appeared in the March/April volume of the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society and will form the basis of his upcoming address at Icarus Interstellar’s 2013 Starship Congress in August. [Super-Fast Space Travel Propulsion Ideas (Images)]

“The proof of principle for FTL space warp propulsion was published decades ago,” said Davis, referring to a 1994 paper by physicist Miguel Alcubierre. “All conventional advanced propulsion physics technologies are limited to speeds below the speed of light … Using an FTL space warp will drastically reduce the time and distances of interstellar flight.”

Warp speed: a primer

Before delving into Davis’ study, here’s a quick review of faster-than-light space travel:

According to Einstein’s theory of special relativity, an object with mass cannot go as fast or faster than the speed of light. However, some scientists believe that a loophole in this theory will someday allow humans to travel light-years in a matter of days.

In current FTL theories, it’s not the ship that’s moving — space itself moves. It’s established that space is flexible; in fact, space has been steadily expanding since the Big Bang.

By distorting the space around the ship instead of accelerating the ship itself, these theoretical warp drives would never break Einstein’s special relativity rules. The ship itself is never going faster than light with respect to the space immediately around it.

Davis’s paper examines the two principle theories for how to achieve faster-than-light travel: warp drives and wormholes.

The difference between the two is the way in which space is manipulated. With a warp drive, space in front of the vessel is contracted while space behind it is expanded, creating a sort of wave that brings the vessel to its destination.

With a wormhole, the ship (or perhaps an exterior mechanism) would create a tunnel through spacetime, with a targeted entrance and exit. The ship would enter the wormhole at sublight speeds and reappear in a different location many light-years away.

In his paper, Davis describes a wormhole entrance as “a sphere that contained the mirror image of a whole other universe or remote region within our universe, incredibly shrunken and distorted.”

Sci-fi fans, for warp drives, think “Star Trek” and “Futurama.” For wormholes, think “Stargate.”

[See also: Warp Drive and Transporters: How ‘Star Trek’ Technology Works (infographic)]

Mirror, mirror on the hull

The next question is: how to create these spacetime distortions that will allow vessels to travel faster than light? It’s believed — and certain preliminary experiments seem to confirm — that producing targeted amounts of what’s called “negative energy” would achieve the desired effect.

Negative energy has been produced in a lab via what’s called the Casimir effect. This phenomenon revolves around the idea that vacuum, contrary to its portrayal in classical physics, isn’t empty. According to quantum theory, vacuum is full of electromagnetic fluctuations. Distorting these fluctuations can create negative energy.

According to Davis, one of the most promising methods for creating negative energy is called the Ford-Svaitermirror. This is a theoretical device that would focus all the quantum vacuum fluctuations onto the mirror’s focal line.

“When those fluctuations are confined there, they have a negative energy,” said Davis. “You could have types of negative energy that could make a wormhole that you could put a person through and, if you make a bigger mirror, put a starship through. The [mirror] is scalable … that’s the beauty of it.”

Davis described a theoretical configuration of Ford-Svaiter mirrors that could enable FTL spaceflight: “For a traversable wormhole, it’ll have to be separate Ford-Svaiter mirrors [arranged] in an array to create the wormhole and then a ship with mirrors attached to it to extend the wormhole to the destination star.”

The concern there is how to target the wormhole’s exit.

“We don’t know the answer to that question yet,” said Davis. “Einstein’s theory of general relativity doesn’t answer it.”

That’s the difference between the fields of physics and engineering, Davis explained. According to our current understanding of physics, targeting the wormhole’s exit is possible, but engineers have yet to figure out how to achieve it. [See also: NASA Turns to 3D Printing for Self-Building Spacecraft]

“On screen, Number One.”

Another issue addressed in Davis’ paper is how to navigate an FTL starship.

“If you’re in a wormhole, you don’t go faster than light — you’re going at normal speeds, but your visualization and stellar navigations are all gone [because] … there are no stars to navigate by.”

The iconic image of stars streaking by a spaceship viewscreen popularized by franchises like “Star Trek” and “Star Wars” simply isn’t accurate, said Davis. “The light that goes through the wormhole gets distorted … you’re going to have a very weird visual display.”

This is because the negative energy necessary to create a wormhole or warp drive creates a repulsive gravity that distorts light around the ship.

So ships moving at faster-than-light speeds will not be able to observe their surroundings to calculate their location. Astronauts will have to rely on sophisticated computer programs to calculate their probable location. “You’ll need something on the order of a supercomputer equipped with parallel processing,” said Davis. “[The computer is] going to have to do all the figuring out … [using] input data from the last position and estimating.”

This is more of a concern with warp drives, which are actively reshaping space as they travel, but not as much with traversable wormholes, whose entrances and exits will probably be preset before flight. “You can only go one way through the wormhole, so it’s not like you’re going to get lost,” said Davis

It’s also important for the computer to be able to produce some kind of visual representation of its flight plan and spatial location. These images would then be rendered and displayed in the starship’s cockpit or bridge for the crew to see and study. “It’ll help the human psychological need for understanding, in real time, what the position changes of the stars are going to look like,” said Davis.

Where no one has gone before

At the heart of Davis’ paper is the principle — supported by rigorous scientific theory — that faster-than-light travel is a real and even tangible possibility. The last section of the paper proposes nine “next steps” that would push the field toward engineering prototypes and other practical tests of faster-than-light theories.

These steps include creating computer simulations to model the structure and effects of space warps. Davis also calls for more rigorous exploration of the Ford-Svaiter mirror, which is still a largely theoretical device. The mirror is just one possible way to generate negative energy; further study is needed to determine whether there are any other practical methods of achieving the same effect. [See also: Hypersonic ‘SpaceLiner’ Aims to Fly Passengers in 2050]

Davis describes the development and implementation of space-warp travel as “technically daunting” in his paper, but in conversation, he said he has no doubt that faster-than-light travel will someday be not only possible, but necessary.

“The Earth is subjected to natural and outer space and ecological disasters, so life is too fragile, while the planets in the solar system are not very hospitable to human life. So we need to explore extrasolar planets for alternative homes,” Davis said.

“This is all part of the growth and evolution of the human race.”

Email jscharr@technewsdaily.com or follow her @JillScharr. Follow us @TechNewsDaily, on Facebook or onGoogle+.