per:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/jul/09/nasa-voyager-solar-system-edge

The edge of the solar system has no edge, it turns out. It has a fuzzy transitional area, not quite solar system and not quite interstellar space.

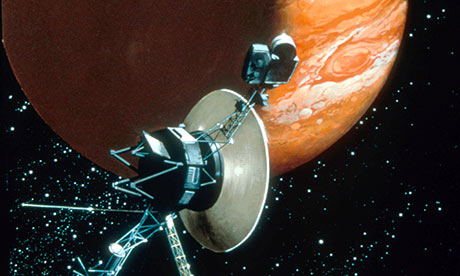

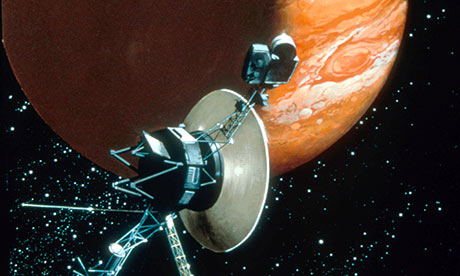

This basic fact of our star’s environment has been discovered byVoyager 1, one of the most remarkable spaceships ever built. Our premier scout of deep space, Voyager 1, is currently 11bn miles from the sun, beaming data to Earth as it scoots at 24,000kmph toward the constellation Ophiuchus.

Scientists had assumed that Voyager 1, launched in 1977, would have exited the solar system by now. That would mean crossing the heliopause and leaving behind the vast bubble known as theheliosphere, which is characterised by particles flung by the sun and by a powerful magnetic field.

The scientists’ assumption turned out to be half-right. On 25 August, Voyager 1 saw a sharp drop-off in the solar particles, also known as the solar wind. At the same time, there was a spike in galactic particles coming from all points of the compass. But the sun’s magnetic field still registers, somewhat diminished, on the spacecraft’s magnetometer. So it’s still in the sun’s magnetic embrace, in a sense.

This unexpected transitional zone, dubbed the “heliosheath depletion region,” is described in three new papers about Voyager 1 published online last month by the journal Science.

“There were some surprises,” said Ed Stone, who has been the lead scientist of Nasa‘s Voyager program since 1972. “We expected that we would cross a boundary and leave all the solar stuff behind and be in all the interstellar stuff. It turned out, that’s not what happened.” So, how big is this transitional zone at the edge of the solar system?

“No one knows,” said Stone, 77, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology and the former head of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Voyager’s home base. “It’s not in any of the models. We don’t know. It could take us a few more months, it could take us several more years to get through it.”

The dimensions and nature of the heliosphere are not a wholly esoteric matter. The sun’s magnetic field deflects much of the radiation coming from other parts of the galaxy that was created in supernova explosions. Interstellar space is not a benign environment. The heliosphere’s features make life easier for blue planets such as Earth.

Voyager 1 can be counted as one of the great exploratory craft in history, and none has gone farther, nor cruised steadily at such astonishing speed (a few have briefly gone faster while falling into the sun). Two Voyager probes were launched in 1977. Both spaceships carried a gold-plated record crammed with digital information about human civilization, including mathematical formulas, an image of a naked man and woman, whale vocalizations, and clips of classical and rock-and-roll music. (The famous joke was that the aliens listened to the record and replied, “Send more Chuck Berry.”)

The two Voyagers embarked on what was called the Grand Tour, taking advantage of an orbital positioning of the four outer planets that happens less than once a century. Voyager 1 flew by Jupiter and Saturn before angling “north,” as astronomers would describe it. (There’s no up or down in space, but there is a north or south relative to the orbital plane of the planets.) Voyager 2 went past Jupiter and Saturn and flew by Uranus and Neptune before heading “south.”

The images of those planets and their moons, now taken for granted, were stunning triumphs of the Voyager mission. And in 1990, Voyager 1, nearly 4 billion miles from the sun, turned its camera toward Earth and took an image of what Carl Sagan called the “pale blue dot” of our home planet.

Now Voyager 1 is 124 astronomical units from the sun – one AU being roughly the mean distance from Earth to the sun, or about 150m kilometres. Voyager 2 is at 102 AU.

These spacecraft are not immortal, even if sometimes they act like it. They have a power supply from the radioactive decay of plutonium-238, which generates heat. The half-life of that system is 88 years. Small thrusters occasionally are fired to keep Voyager 1’s 23-watt radio antenna pointed toward Earth, where the faint signals are picked up on huge arrays of radio telescopes in the United States, Spain and Australia. But Stone anticipates that weakening power will force scientists to start shutting down scientific instruments on Voyager 1 in 2020 and that by 2025, the last instrument will be turned off.

“It changed the way we view our place in the cosmos,” said Bill Nye, the “Science Guy” who is chief executive of the Planetary Society in Pasadena, Calif. He said the new discovery by Voyager 1 is a classic example of why we explore: “What are you going to find over the unknown horizon? We don’t know. That why we explore out there.”

NASA’s associate administrator for space technology, Michael Gazarik, said of Voyager 1’s durability: “It is amazing, especially in the harsh environment of space. This piece of hardware has a life of its own.”

In 40,000 years, Voyager 1 will be closer to another star (with the romantic name AC+79 3888) than to the sun. And then what? It will just keep going – a silent, dark craft on a seemingly eternal journey.

“It will be orbiting the center of the Milky Way galaxy essentially for billions of years, like all the stars,” said Stone of what has been, for him, the spacecraft of a lifetime.